The near-simultaneous rise of interest in open source and open access in the context of academic libraries has made these concepts ripe for confusion. Adding to the confusion is the presence of projects that are both open source and open access. Rather than cringing in silence when these terms are used interchangeably, I’m hoping to clarify the conversation. Note: I’m not an expert in either concept, so please feel free to research more and/or to add your comments.

Open Source

Open source refers to exclusively to software. It means that the source code for that software is openly available, thus allowing for modification, and that the software may be redistributed freely. (As a side note, the related term “free software” refers to the users’ freedom to copy, run, distribute, and modify software, rather than meaning free of cost.) Much open source software is free of cost, but some applications do carry licensing fees. If, as a library, you care about purchasing software to which your programmers can make modifications on the back-end, then use the term “open source.” But if all you really want is to use something that doesn’t cost you anything, just say so.

Open Access

Open access (or OA) refers to unrestricted public access, usually in the context of research. This has made particularly big headlines in science (where published research is remarkably expensive and takes up a large percentage of library budgets, thus unattainable to the public except through library membership) and specifically in medicine, where some open access research has led to breakthroughs (like 16-year-old Jake Andraka’s cheap cancer sensor). For an in-depth definition of OA, see Peter Suber’s great introduction. (Peter Suber also has a great summary of OA myths.)

There are several reasons why open access is such a hot topic in academia, and specifically in libraries. First, it addresses intellectual rights issues (hence the “unrestricted” part of the definition). Since authors typically relinquish their copyright for published works (more on this later), many interpret copyright law that they do have the right to use that work (in its entirety) in the classroom. (This is part of the ongoing debate of the meaning of the “fair use” doctrine.) Open access, often in concert with Creative Commons licenses, makes work available for access, copying, distribution, and reuse.

Second, as library budgets continue to decrease, the cost of purchasing published research is skyrocketing. Publishers continue to raise journal subscription rates, causing academic libraries to make tough choices about what to keep and what to cut. That limits the research to which their faculty have access.

Third, when academic libraries subscribe to journals, many times they are effectively “buying back” the research performed by their institution’s faculty. The markup and re-selling of that knowledge by publishers is increasingly looked upon by academics with a skeptical eye. Thus, libraries are turning to scholarly repositories (where faculty can store and share pre-printed versions of their research) and open access publishers to find new models for disseminating scholarship.

Open access is commonly referred to as “free” access, but that’s only part of the story. Usually someone does have to pay something to store, host, and share information, even when it’s not distributed in print format. With open access, these costs are not born by the consumer (the public)—instead, there are a few different models of who pays the costs.

Green OA: Institutional repositories (IRs)

Versions of traditionally published works (usually preprints or postprints) are deposited in an institutional repository (IR). They exist alongside the traditionally published version of the work. Since it is typical practice for academic publishers to require transfer of author copyright as part of the publication process, authors usually get permission to archive their work in IRs in one of two ways. The first is to not relinquish their copyright in the first place, typically expressed through an addendum to a typical publishing agreement—SPARC has a great example and an easy online form to create your own. The second is to request permission to post a preprint or postprint (or to publish with a publisher who provides for this circumstance in their general policy). (Of course, even this option is not “free,” since creating and maintaining an IR takes equipment and staff time.)

Gold OA: OA journals

In the gold model, either the publisher or the author pays the publication cost up-front to make the work freely available in a journal. In practice, author fees are often paid by research grant funds, academic departments, or libraries, but may be paid by the individual. Increasingly, the journals themselves have adequate funding and do not require author fees.

Crossover

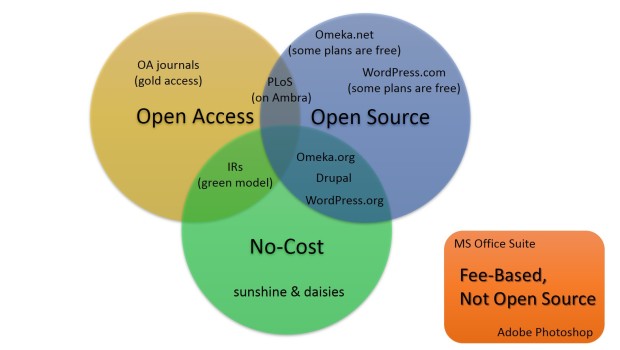

So while open source and open access are different concepts, they are related in their dedication to openness, and they sometimes overlap in a single project. For instance, PloS (Public Library of Science) is an open access journal (gold) that is hosted on an open source software platform (Ambra).

Examples

This is already present in the Venn Diagram, but here are the examples I could think of while writing…

- OA + OS: PLoS (hosted on Ambra)

- OA (gold): BioMed Central

- OA + No-cost (green): most IRs, for instance Columbia’s Academic Commons or UNT’s Scholarly Works

- OS: Omeka.net (some plans are free), WordPress.com (some plans are free)

- OS + No-cost: Omeka.org, Drupal, WordPress.org

- None of the above: MS Office Suite, Adobe Creative Suite

You can find more examples of OA publications and IRs at ROAR and SHERPA/RoMEO.

Conclusioniatory Remark

To sum up: perhaps we should never use the word “free” in conversation, it’s too confusing! I do like this example given for explaining “free software,” however—it’s more like “free speech” than like “free beer.”

I know this post is old, but I just read it for the second time today, and I feel compelled to add that open source does not necessarily mean that “programmers can make modifications on the back-end” since that depends on how the code has been licensed. However, it always means that you can see the code, and thus, you are much more likely to be able to design homemade tools to work with the open source software. Open source also supports various digital stewardship activities (with closed source software many of these activities are impossible).

I really appriciate your outline of different kinds of OA and your work to distinguish these oft-conflated terms.

For most up-to-date information you have to visit world-wide-web and on internet I found this site as a finest web page for latest updates.|

Please approve me

Ty mate

Sorry but your explanation of the differences between “open source” and “free software” are wrong. Free is not about the price. As we usually say “Free Software is free as free speech, but not as free beer”.

So, long story short, the main difference is “open source” is mainly concerned about the code been open, while free software is worried about “freedom”.

This old article explains the difference quite well:

https://www.gnu.org/philosophy/open-source-misses-the-point.en.html